By: Juliet Buna

Email: bunajuliet23@gmail.com

“Hello Aunty, good evening… That story, I don’t want to have anything to do with it again. People are calling my mother, they are threatening her…” the caller said with a trembling voice and the call ended abruptly.

Sighs…

The phone call was brief, but the desperation was palpable.

That was 16-year-old Alice (not real name) in May 2024, rescinding her decision to share her sexual abuse story with the world, thereby shutting the door against the possibility of getting elusive justice.

Prior to this phone call, Alice and her two friends, all minors, were eager to share their harrowing experiences of the sexual abuse endured at the hands of their secondary school proprietor, in Ondo State, Southwest Nigeria. A man they said they once saw as a tutor and a father figure.

When Alice and her friends withdrew from the story, their parents, who had initially given consent for their children to be interviewed, also called the journalist to announce their withdrawal. According to them, “He will change, “.

And then, the final blow came: citing a spiritual attack, one of their former teachers, who had risked everything to provide evidence and connect the girls to the media and other civil society organisations in their quest for justice, also withdrew from the case.

Could the girls and their parents have been threatened by their abuser or promised some sort of compensation to protect their abuser? Many say it is not impossible, but all of that would never compensate for the innocent lives that have been ruined.

Prevalence of Sexual and Gender-based violence in schools

These young survivors, already burdened by the trauma of their experiences, now face the added weight of personal safety concerns, potentially leaving their stories untold and the potential risk the unchecked abuser poses to society and many other young girls out there.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates that one in 10 children worldwide are sexually abused. Rape within the family is particularly difficult for the victim and in almost 60 per cent of cases, the victim was unwilling to report the abuser.

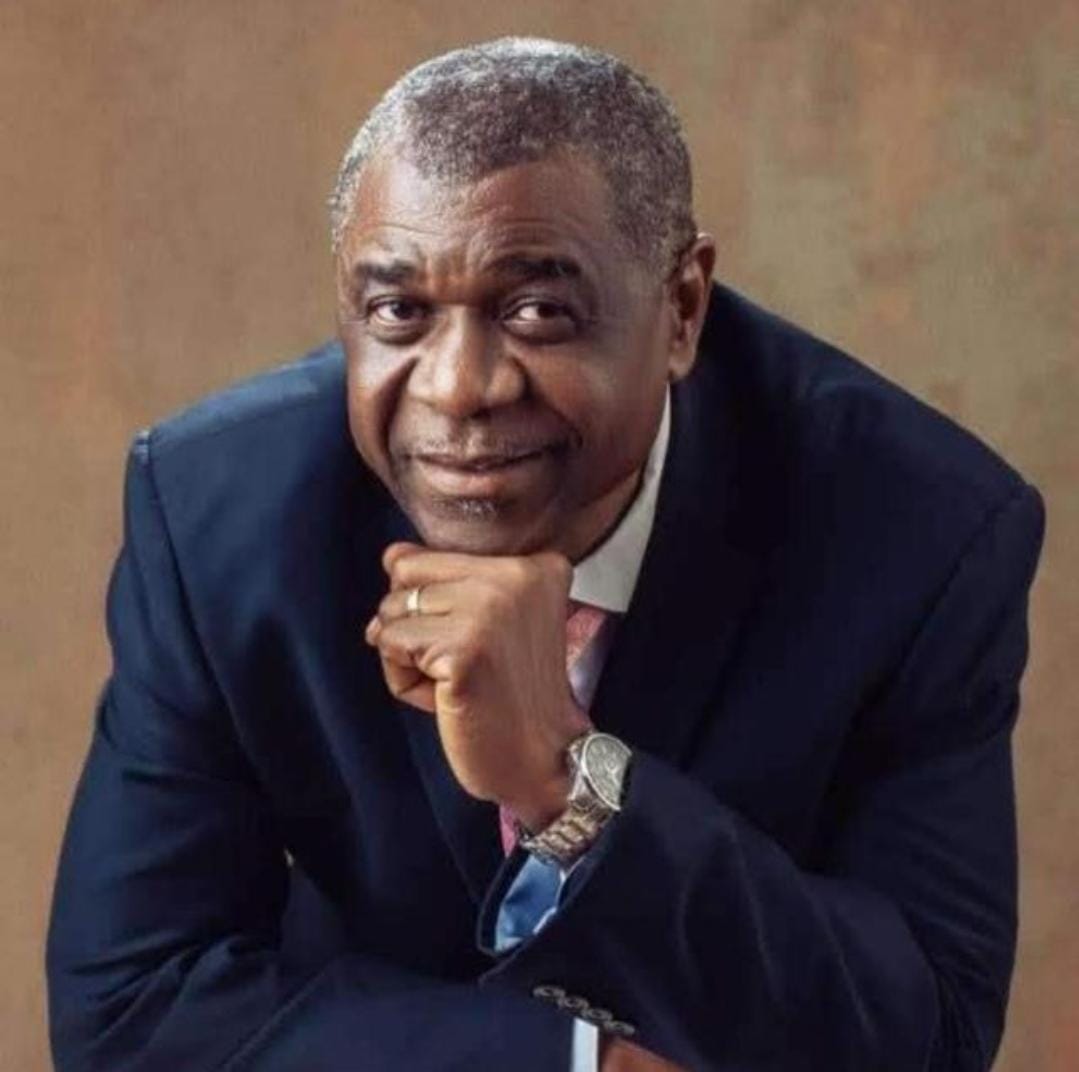

The Chairman of the Independent Corrupt Practice and Other Related Offences Commission (ICPC), Dr Musa Adamu Aliyu (SAN), expressed concern about the increasing incidents of sexual harassment in primary and secondary schools across the country during a stakeholders’ meeting on July 9, 2024. According to The Guardian Nigeria, Aliyu stated, “It is alarming to note that sexual harassment, commonly associated with tertiary institutions, is also prevalent in primary and secondary schools.”

Sexual Harassment, a pervasive issue in Nigerian academic institutions, affects both students and staff, causing humiliation, degradation, and hostility. The unacceptable behavior ranges from ogling, touching, and inappropriate comments to sexual propositions, coercion, assault, and rape.

A 2018 World Bank survey revealed that 70% of female graduates from Nigerian tertiary institutions experienced sexual harassment from fellow students and lecturers

Despite the increase of sexual harassment in schools and other places in Nigeria, a bill aimed at criminalizing sexual harassment in tertiary institutions has been stuck in the National Assembly for eight years.

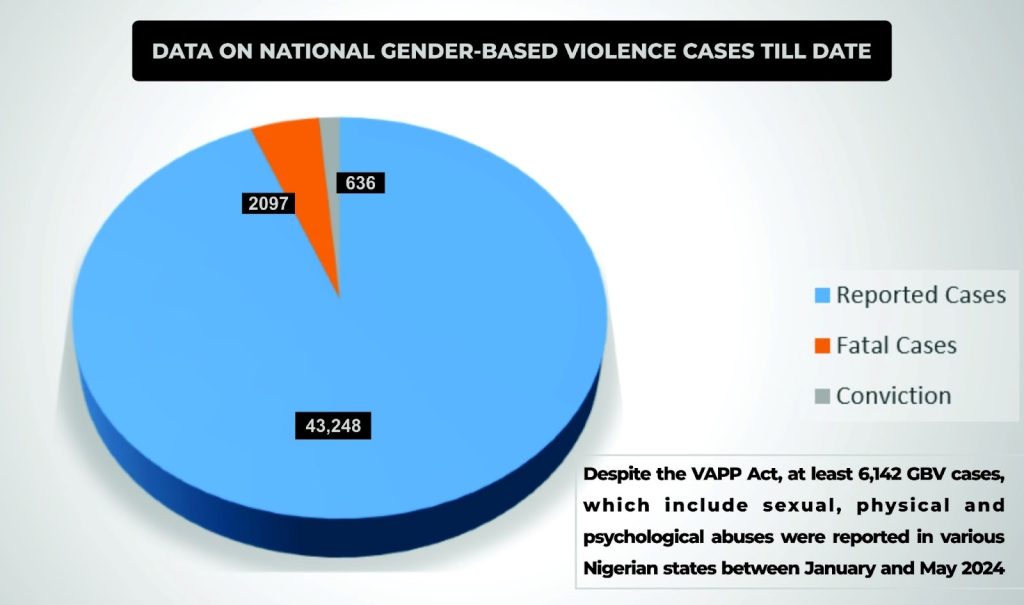

Data from the dashboard of the national gender-based violence dashboard: Graphics by Juliet Buna

The “Sexual Harassment in Tertiary Education Institution Prohibition Bill” was first introduced in 2016 by former Deputy Senate President Ovie Omo-Agege and 57 other senators. It proposed jail terms for educators found guilty of sexually harassing their students.

The Bill faced opposition from the Academic Staff Union of Universities, citing concerns about institutional autonomy. Then House Speaker, Femi Gbajabiamila, suggested expanding the bill to cover other institutions, leading to its “initial withdrawal’’

The Bill was re-introduced and passed by both the Senate (2020) and House of Representatives (2022). In 2023, the National Assembly jointly passed the Bill, paving the way for presidential assent and potential enactment into law.

Despite the Bill’s passage in 2023, a new National Assembly was inaugurated shortly after, resetting the legislative process. To become law, the Bill must be re-introduced and re-passed by both chambers, as President Bola Tinubu cannot grant assent to Bills carried over from the previous assembly. This procedural requirement delays the Bill’s enactment, pending its re-introduction and re-approval by the new legislative body.

Data from the national gender-based violence dashboard website showed that to date, there have been 43,248 reported cases of GBV with about 2,097 being fatal cases, and the conviction of 636 perpetrators.

Despite the VAPP Act, at least 6,142 GBV cases, which include sexual, physical and psychological abuses were reported in various Nigerian states between January and May 2024.

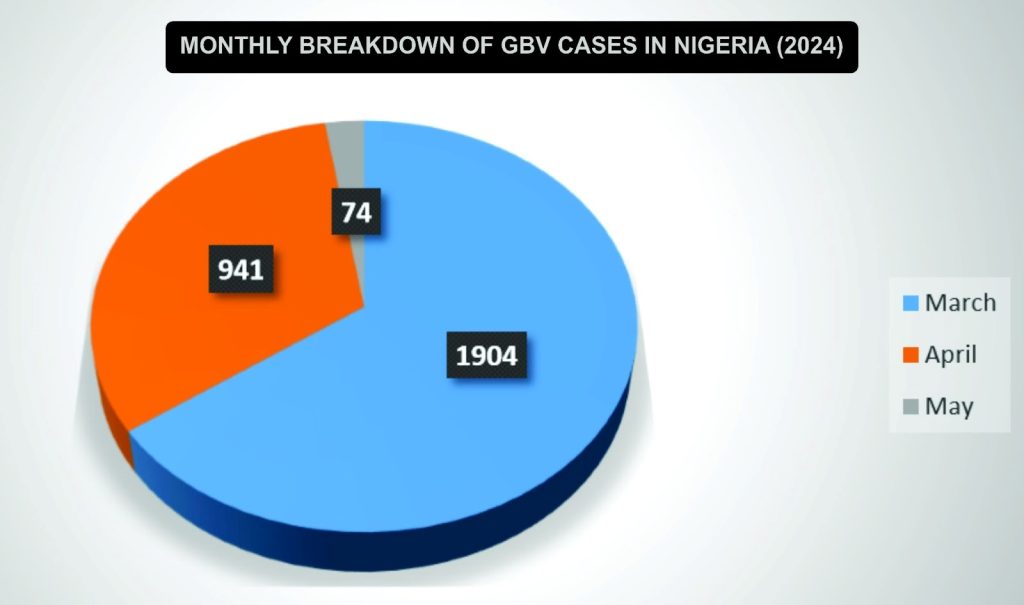

Data from the dashboard of the national gender-based violence dashboard: Graphics by Juliet Buna

The monthly breakdown of GBV cases across the 36 states and the Federal Capital Territory in 2024 revealed that 74 cases had been recorded in May, with 941 cases in April, while March saw a significant spike with 1,904 cases.

Why Do Women and Girls Fear Speaking Out Against SGBV?

Alice and her friends’ decision to withdraw from telling their stories exposes the pervasive culture of silence and fear that often surrounds cases of abuse, especially when the perpetrators hold positions of power and influence.

In Nigeria and other parts of Africa, reporting cases of sexual assault was not the norm until over a decade ago when government and civil society groups started pushing for legislation to ensure stricter punishment for offenders and also encourage victims and their families to speak out. Despite these efforts, sexual abuse cases are still believed to be underreported, especially in rural communities.

A report by the U.S National Online Resource Center on Violence Against Women, identified the problem of confidentiality for victims, isolation, high degree of familiarity between victim and perpetrator and cultural attitudes such as a frequent distrust of outside help, as some of the reasons why there are low reports of sexual assaults in rural areas.

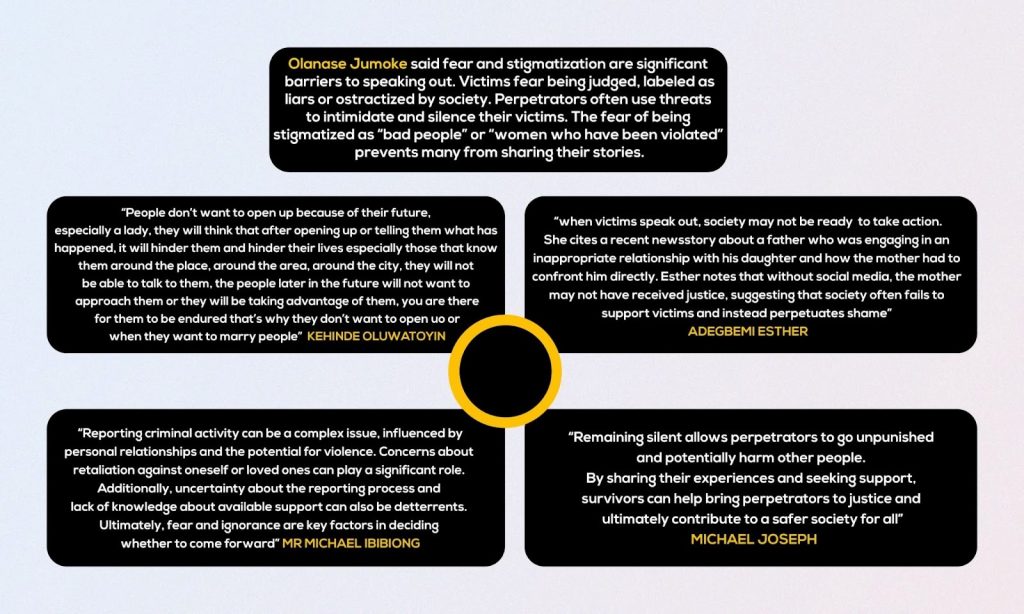

In Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria, several individuals revealed some reasons why women and girls often hesitate to share their experiences of gender-based violence (SGBV).

Graphical representation of responses from residents of Ibadan: Source: Juliet Buna

Has the Culture of Silence Affected the Justice System?

Proving sexual offenses in court is a daunting task that often discourages victims from coming forward. The burden of proof heavily lies on the prosecution, requiring solid evidence such as forensic data, witness testimonies, and the victim’s account. This process can be re-traumatizing during cross-examination, and the high standard of proof beyond a reasonable doubt further complicates the pursuit of justice.

Despite these challenges, various measures are being undertaken across Nigeria to support victims. The Lagos State Domestic and Sexual Violence Response Team (DSVRT) leads these efforts, offering advocacy and support. In Kaduna State, a law mandates the castration of those convicted of raping minors under 14. Additionally, 34 states and the Federal Capital Territory (FCT) have domesticated the Violence Against Persons Prohibition (VAPP) Act 2015 to curb violence.

Notable convictions in high-profile cases highlight the importance of persistent legal efforts. For instance, Nollywood actor Baba Ijesha was convicted of sexually assaulting a minor, and a former supervisor at Chrisland School in Lagos was sentenced for sexually abusing a minor.

A Nigerian lawyer Temitayo Adedeji emphasized the critical importance of ensuring justice for all parties involved. “Justice is three-way traffic: justice for the accused, justice for the victim, and justice for the state or society,” Adedeji stated.

He highlighted that the criminal justice process, starting with the victim reporting an offense, ensures that all individuals are treated with dignity and respect, as protected by Sections 34 and 42 of the 1999 Constitution.

He said, “There is this culture of silence thereby if because of societal pressure or fear or other factors victims are been silenced and this has an impact on the judicial process also one of the effects of cultural silence is it will let justice take its course in that when victims are silenced either by societal norms, fear or other factors, it prevents justice from the search on the accused, remember what I said is that one of the attributes of criminal justice says that an accused person, an offender must not go unpunished and should be punished for the offense he is alleged to have committed.”

What can be done to curb the menace?

An Educationist, Mrs Oluwatoyin Adegbenro thinks that speaking out is the first step in addressing and curbing the menace.

According to her, when a child discloses abuse to a trusted individual, it opens the door to taking appropriate actions to address the situation. She said that improper handling of such cases can lead to the victim’s identity being exposed, resulting in social stigmatization

Mrs Adegenro explained that staying silent is not the best course of action, as it affects the victim’s emotional well-being and self-esteem adding that parents are advised to escalate the issue to the Parent Teacher Association (PTA) or the Ministry of Education, regardless of whether the school is public or private.

“There are rules in the teaching profession that guide against this kind of practice a lot of time is either the teacher gets dismissed, a lot of cases too they can get demoted and they can even get sacked, that is why you see that when this kind thing happens, they get begging the parent not to talk.”

A Girl Child Advocate, and the Chief Executive Officer of Kids and Teen Resource Center, Akure, Ondo State, Nigeria, Martin Mary-Falana, said his organisation has encountered challenges with the police, who often fail to adequately address abuse cases. He said neglecting such cases leads to further victimisation of the children.

“It’s been challenging having a case of abuse and at the end of the day, the person abused is the one saying I am not interested again. The injustice we see, most times is in the police, the perpetrator bribes them with a little token of #5000 or #2000, telling them what to write during the purely unfair interrogation, especially on the survivor who would bear the cross of their act after the incident. So, most times, we don’t report to them, we report to the civil defense who can give quick responses.”

The Operations Manager at Hope Behind Bars Africa, Okeke Grace Eche called for urgent reform in Nigeria’s criminal justice system to address the culture of silence surrounding sexual violence.

According to her: “Nigeria’s criminal justice system is plagued by slow access to justice, perpetuating a culture of silence around sexual harassment and violence. numerous cases of sexual abuse, detention abuses, and human rights violations by law enforcement officials have gone unreported. Young Nigerians, especially women, have been forcibly taken and exploited, while perpetrators with criminal mindsets remain unaccountable. When a young woman reports harassment, she often faces a lack of tangible justice, leaving her feeling unheard and unsupported. Justice is not just about punishing the perpetrator but also about acknowledging the victim’s suffering and providing recourse. The government’s inaction emboldens criminals and silences victims, perpetuating a culture of fear and oppression.”

Psychological Impact of silence on Survivors of abuse

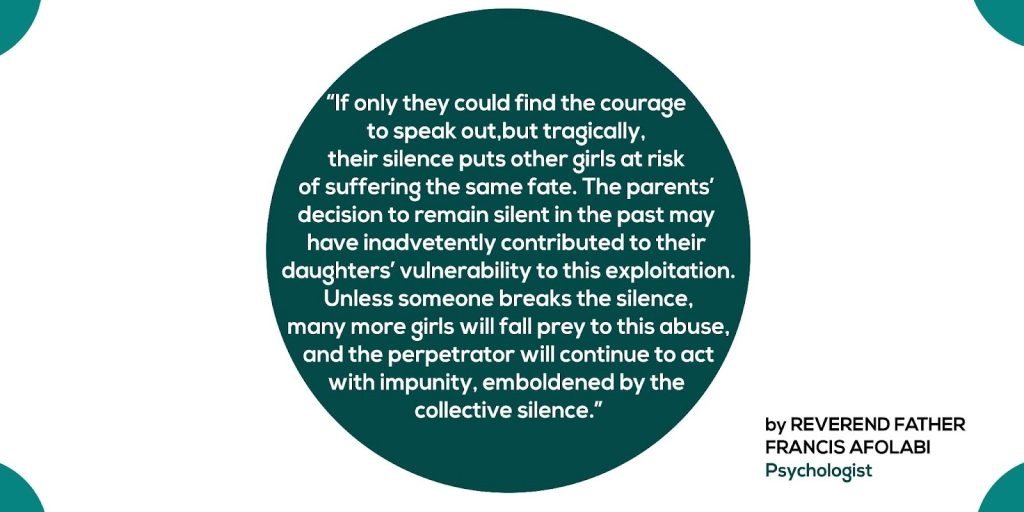

A Psychologist, Reverend Father Francis Afolabi, warned that the culture of silence can lead to low self-esteem, excessive self-consciousness, and traumatization, causing individuals to become toxic parents, teachers, and leaders. He lamented that the fear of stigmatization and labeling leads people to keep quiet about their traumas, difficulties, and challenges, ultimately causing them to internalize their pain and become maladjusted.

“As a result, they become overly self-conscious, constantly worried about what others say or do around them. They tend to link every experience to their past trauma, even if it’s not relevant because they haven’t spoken up and are bottling up their emotions. This ultimately leads to traumatization, causing them to feel stuck and unable to move on. They feel insulted, used, and objectified, leading to withdrawal from reality. Unfortunately, this behavior will perpetuate, and they will become toxic parents in the future, passing on their unresolved pain and trauma to the next generation. Their unresolved experiences have taken hold of their personality, and they fail to seek help even when it’s available.”

Way Forward

The Girl Child Advocate, Martin Mary-Falana, revealed that his organisation works closely with the Nigeria Security and Civil Defence Corps and the International Federation of Women Lawyers to provide a safe and confidential platform for children to share their experiences.

According to him, the center’s strategy involves general sensitization in schools and anonymous reporting, where children can write down their problems on a sheet of paper without fear of retribution. He said the organisation recorded 57 cases of abuse between 2022 and 2024.

“We give them a sheet of paper to anonymously write down the problems they are facing, and send it to us,” he said”. “So nobody knows who is doing what, we answer the questions without mentioning the name of that particular person who wrote the question, that’s the unique approach we take, which sets us apart from other organizations.”

Reverend Afolabi, emphasized that breaking the culture of silence is crucial, especially for parents who must create a safe space for their children to speak up. He advised parents to confront their own past experiences and trauma, rather than perpetuating the cycle of silence.

“This story is part of the African Women in Media (AWiM) ‘Reporting Violence Against Women and Girls in Nigeria’ project, supported by the Wole Soyinka Centre for Investigative Journalism.”